Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Majors' capital allocation in a stuttering energy transition

NOCs now carry the torch for low carbon investment

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Oil’s resilience in the energy system

-

Opinion

Five key takeaways from our Gastech 2025 Leadership Roundtables

-

The Edge

Five key takeaways from COP30

-

The Edge

Can copper supply keep up with surging demand?

-

The Edge

ADIPEC 2025: six key takeaways

-

The Edge

Slipping climate targets and the “energy addition”

Luke Parker

Vice President, Corporate Research

Luke Parker

Vice President, Corporate Research

Luke is Vice President of Corporate Research with a specific focus on the Supermajors.

Latest articles by Luke

-

The Edge

US Lower 48 upstream: the US Majors’ long-term strategic advantage

-

The Edge

Majors' capital allocation in a stuttering energy transition

-

Opinion

Video | Shell and Equinor announce UK asset merger to create new JV

-

Opinion

Beyond ESG: measuring corporate sustainability in an uncertain world

-

The Edge

Big Oil: upstream M&A gets serious

-

Opinion

Are NOCs prepared for the energy transition?

Greig Aitken

Director, Corporate Research

Greig Aitken

Director, Corporate Research

With over 12 years of experience, Greig brings a holistic view of corporate activity to the upstream M&A research team.

Latest articles by Greig

-

Featured

Corporate oil & gas 2026 outlook

-

Opinion

What’s been happening in upstream M&A?

-

The Edge

Majors' capital allocation in a stuttering energy transition

-

Featured

Upstream M&A 2025 outlook

-

Opinion

Ten key considerations for oil & gas 2025 planning

-

Featured

Upstream M&A 2024 outlook

Tom Ellacott

Senior Vice President, Corporate Research

Tom Ellacott

Senior Vice President, Corporate Research

Tom leads our corporate thought leadership, drawing on more than 20 years' industry knowledge.

Latest articles by Tom

-

Featured

Corporate oil & gas 2026 outlook

-

Opinion

Power moves: TotalEnergies’ Integrated Power strategy assessed

-

The Edge

Majors' capital allocation in a stuttering energy transition

-

Featured

Corporate oil & gas 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

The complexity of capital allocation for oil and gas companies

-

Opinion

Ten key considerations for oil & gas 2025 planning

Judging the pace of the energy transition has been perhaps the biggest strategic conundrum for oil and gas companies since the Paris Agreement almost 10 years ago. European Majors have led the way, early movers in allocating capital away from oil and gas into low-carbon opportunities.

BP’s decision this week to slash its investment in low carbon confirms what’s been evident in the last three years as the energy transition has hit headwinds: the risk/reward ratio doesn’t make sense for oil and gas investors. Luke Parker, Greig Aitken and Tom Ellacott of our Corporate Analysis team shared their thoughts with me.

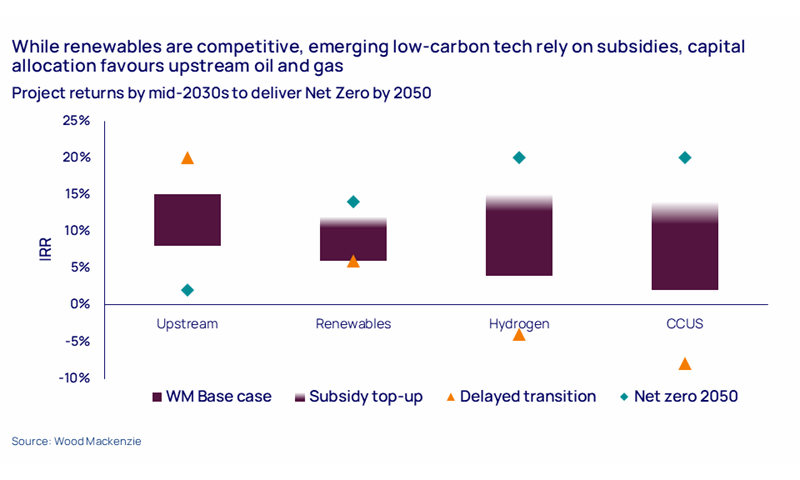

First, current project economics heavily favour investment in upstream over low carbon (see chart)

Some low-carbon technologies are investable – solar and onshore wind, for example, after two decades of massive cost reductions. The returns, though, are comparatively modest. BP’s planned offloading of its entire renewables business – selling US onshore wind, moving offshore wind and solar into ring-fenced JVs – speaks volumes of the oil Majors’ priorities.

Emerging technologies including blue and green hydrogen and carbon capture and storage are all at a much earlier stage of development. Most require years of investment and innovation to replicate solar’s downward cost trend, plus heavy subsidies until they achieve stand-alone commerciality in the mid-2030s.

Governments – consumed by more urgent priorities, including defence and the cost-of-living crisis – are struggling to justify the scale and duration of the subsidies these emerging technologies need. On the other side of the equation, companies seeking to invest cite a lack of visibility on subsidies as a blocker to progress.

Some Euro Majors adopted low-carbon strategies that embraced multiple technologies. While there is an argument for spreading risk, it’s led to perceptions of a lack of focus.

Upstream projects, in contrast, can look highly attractive in the current environment. The slow pace of the transition implies stronger-for-longer oil and gas demand and the prospect of firm oil and gas prices. That combination underpins double-digit returns for Wood Mackenzie’s pipeline of pre-FID projects.

The financial framework for the Euro Majors, as with the US Majors, is still bound by strict capital discipline – capital will only be allocated to the opportunities with the highest risk-adjusted returns. With most of these in upstream, spend on low carbon and renewables is being squeezed.

Second, the global outlook for investment in energy supply also reflects a softening enthusiasm to invest in low-carbon

opportunities

Investment in power and renewables, upstream oil and gas and critical metals for the transition continues to rise. We forecast a 6% increase this year, lifting spend to a record US$1.5 trillion. Low carbon’s share of the total jumped from 32% in 2015 to 50% in 2021 but has stalled since and won’t increase on our forecasts until the end of the decade. It needs to be 60% higher than the current US$0.7 trillion a year by 2030 to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement on our estimates.

The Euro Majors’ cutbacks in low-carbon investment broadly mirror the global trend. After diverging for years, US and Euro Majors’ spend on low carbon is now converging. The Euro Majors had committed an average of 30% of total investment to lowcarbon projects in 2024, but Shell, Equinor and now BP are rebasing around 15% to 20%. ExxonMobil and Chevron, going in the opposite direction, are now 15% and 10%, respectively.

Third, the Euro Majors’ tilt back to upstream is ultimately pragmatic

Upstream will be in business for much longer than they anticipated in the post-Paris Agreement strategic reset, and there’s still money to be made.

The pivot, though, won’t happen overnight. We still expect the Euro Majors’ to focus on driving up cash flow and dividends to boost stock market ratings. This will increase the financial optionality for large-scale deal-making in 2026. In the meantime, imaginative business development can strengthen the portfolio incrementally as BP’s recent Kirkuk deal in Iraq shows.

Finally, national oil companies’ budgets for low-carbon projects had already eclipsed the Majors in 2024

Collectively, Saudi Aramco, ADNOC, Petrobras, Petronas, PetroChina, CNOOC and ONGC plan to invest over US$20 billion a year through 2030 – albeit for many of these industry giants it’s a much smaller proportion of free cash flow. The scale of the NOCs’ cash generation, overarching national targets to decarbonise and aspirations to diversify their economies away from oil and gas suggest NOCs will carry the low-carbon torch for the oil industry in the next stage of the energy transition.

The global push to a low-carbon world hasn’t stopped; it’s just slowed. It’s possible, even probable, that in a few years’ time, the relative returns will reverse and the Majors ramp up low-carbon investment once again.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.