Is the world sleepwalking into an oil supply crunch?

Where new oil supply to 2030 will come from and what it costs

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Battery energy storage comes of age

-

The Edge

CCUS’s breakthrough year

-

The Edge

Five themes shaping the energy world in 2025

-

The Edge

Renewable developers change tack

-

The Edge

How ultra-deepwater is revitalising oil and gas exploration

-

The Edge

COP29 key takeaways

Underinvestment in oil supply will lead to a tight oil market later this decade. It’s a narrative that’s gained increasing traction as capital expenditure on upstream oil and gas has shrunk. Spend in 2021 is half the peak of 2014 after slumping to new depths in last year’s crisis. I asked Harry Paton of our Oil Supply team and Ann Louise Hittle, Head of Macro Oils, how they see the medium-term market fundamentals developing and the implications for price.

How much new oil supply does the world need?

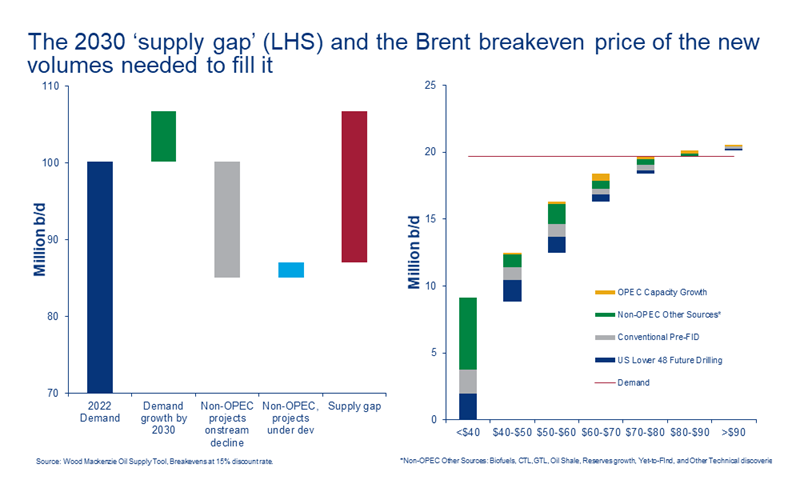

A lot - we reckon about 20 million b/d from 2022 to 2030. This is the ‘supply gap’, the difference between our estimate of demand in 2030 and the volumes we forecast existing fields already onstream or under development can deliver.

Fleshing that out, we expect oil demand to grow from 2022 to 2030, rising by just under 7 million b/d. The rate of growth, though, slows through the period to less than 0.5 million b/d a year by 2030. Non-OPEC onstream supply falls by 13 million b/d over the same period. This is mainly a function of the natural decline of mature assets in big producing countries including the US, China, Russia and Norway.

Our forecasts suggest net OPEC supply growth from 2022 to 2030 is modest.

Where will new supply come from and at what cost?

The supply is there to fill the gap to 2030. Most of the 20 million b/d will come from non-OPEC sources. Around 16 million b/d has relatively low cost, breaking even below US$60/bbl – predominantly reserves growth from developed fields, US Lower 48 drilling and pre-FID projects. The remaining 4 million b/d is mostly from the same sources but higher cost with break-evens ranging from US$60/bbl to US$80/bbl. Other non-OPEC sources also contribute some volumes, including yet-to-find, biofuels, CTL, GTL, oil shale and technical discoveries.

Our forecasts suggest net OPEC supply growth from 2022 to 2030 is modest. Volume increases for Middle East countries partly offset declines in maturing countries including Nigeria, Angola and Algeria.

What are the implications for OPEC?

OPEC’s market share has fallen substantially over the last decade, from just under 40% in 2010 to 30% last year. The ascent of US tight oil through the decade was a big factor, while the pandemic forced OPEC to materially curtail supply in 2020.

The immediate priority for OPEC and its partners in OPEC+ is to balance the market as demand recovers. We expect OPEC will be able to increase volumes progressively through to end 2022. But the scope is more limited in the years beyond, unless global liquids demand surprises on the upside. On our forecasts, OPEC’s market share doesn’t increase much above 32% to 33% for much of the coming decade.

What does it mean for prices?

There are three main drivers behind our forecast for Brent to rise to US$80/bbl (real) later this decade. First, the fundamentals – a price of US$80/bbl is needed to incentivise investment in the higher cost barrels to meet increased demand through to 2030.

Current firm prices are helping OPEC to maximise income and recoup revenue ‘lost’ last year.

Second, limited ‘available’ OPEC spare capacity leaves the market vulnerable to supply disruption. Political risks (Nigeria, Libya) or sanction risks (Iran and Venezuela) threaten to restrict OPEC’s theoretical spare capacity to a more modest ‘available’ capacity of 4 million b/d or 4% of global demand.

Third, there’s OPEC strategy. Current firm prices are helping OPEC to maximise income and recoup revenue ‘lost’ last year. But higher prices incentivise non-OPEC investment at the margin and run the risk of limiting OPEC’s own scope for material future volume increases beyond 2022.

It’s starting to happen in the US. Tight oil’s recovery this upcycle is much more sluggish than previous ones, with publicly listed operators holding the line on capital discipline. Even so, the US Lower 48 rig count has doubled in 10 months from the August 2020 low mainly because private companies, freer of stakeholder ‘stay-flat’ shackles, are spending more. It’s only just enough to keep production static in 2021.

That will change. We expect the rig count in the Permian, the main focus of new drilling, to rise by another 80% in the next 18 months. Higher production will follow. We forecast US Lower 48 production will grow by 2 million b/d from 2022 to 2030 based on Brent steadily increasing to US$80/bbl (real).

OPEC, and Gulf producers in particular, hold the much of world’s lowest cost undeveloped resource. Our analysis suggests the world becomes increasingly reliant on these barrels after 2030 as non-OPEC production plateaus and then declines. This decade though looks more challenging for OPEC as a whole to increase its market share if prices stay at current levels or higher.

Once demand has recovered from the crisis and the market has rebalanced, OPEC may find it can’t have its cake and eat it.