Gas and LNG – approaching a winter reckoning

Global implications of sky high prices

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

What next for East Med gas?

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

-

The Edge

Walking Japan’s energy tightrope

-

The Edge

No country for oil men (and women)

-

The Edge

Battery energy storage comes of age

-

The Edge

CCUS’s breakthrough year

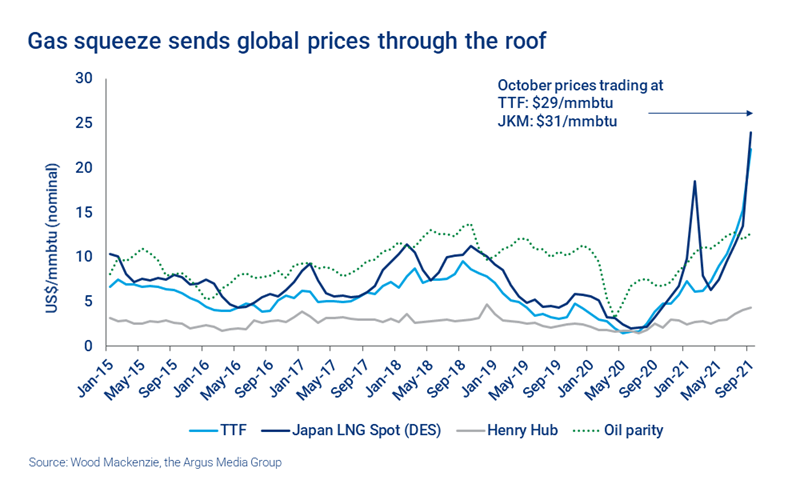

Gas prices have hit record levels in Europe and Asia surging ten-fold in a year. As with all perfect storms, the crisis has come about by creeping incremental factors. Demand is soaring as the global economy recovers; storage is low after last year’s long, cold winter; and there have been numerous supply disruptions, some planned, others not; while Russian pipe gas has been flowing below capacity. Gas supply has also been pulled into power markets, with wind capacity utilisation low in Europe, hydro low in Brazil and China, and with coal and carbon prices rising to all-time highs.

I spoke to Massimo Di-Odoardo, Head of Global Gas Analysis, about some of the global implications.

Will Europe have enough gas this winter?

It depends on how cold and how long a winter we have. Our analysis shows there will be adequate supply in a normal winter. Demand will be kept in check by high prices; pipe supply will be boosted by a recovery in UK and Norwegian production and higher imports from Azerbaijan; new LNG capacity, mainly in the US, will add 7 Bcm to Europe this winter once Asian demand is met. Assuming Russian exports at full capacity, Europe will end up with 29 Bcm of gas in storage by end of March. That’s below the 5-year average but much more than current prices are indicating.

The system creaks if there’s a cold winter in both Europe and Asia. Higher demand for heating could add up to 20 Bcm in Europe and 10.5 Bcm in Asia, resulting in lower LNG imports available to Europe. That would suck up all the gas left in European storage, and gas prices could go much higher than we’ve seen so far.

Russia might be able to supply additional gas either through Nord Stream 2, depending if and when it gets approval; or use its interruptible capacity via Ukraine - something Russia has so far been reluctant to do.

A cold winter would make Europe entirely dependent on additional Russian flows. That’s not a prospect that will help European and UK politicians sleep comfortably at night in the coming months.

Is the crisis a one-off or a sign of structural change?

One-offs have contributed, though structural changes in both power and gas markets are the deeper problem. Europe’s shift away from coal-fired generation has meant greater dependence on gas for flexibility in power; while Europe’s gas supply and flexibility in turn has become increasingly dependent on imported piped gas and LNG.

Europe’s shift away from coal-fired generation has meant greater dependence on gas for flexibility in power.

First, Europe’s own flexible sources of gas dwindled over the last decade as the Groningen field (Netherlands) wound down. The UK also chose to close its biggest storage facility, Rough, in 2017. Second, there’s not only less Russian pipe capacity but long-term contracts with Russia are less flexible, after buyers exchanged upward flexibility for spot indexation. Third, Europe’s relied on the ample growth of LNG volumes for the last few years. A sharp slowdown in investment means very limited global LNG growth through 2025 which is coinciding with strengthening Asian demand.

The upshot of all this is that Europe will be even more dependent on Russia for flexibility, as well as supply.

Can Europe build more flexibility into the system?

Russia would argue that Nord Stream 2 will bring the needed flexibility. But Russia also wants to divert gas away from Ukraine, so overall Russian capacity may not change much.

More LNG will be part of the solution. With prices more than double the US$10/mmbtu delivered cost to Europe (assuming US$5.30/mmbtu Henry Hub), US developers will be scrambling to expedite new projects. But it won’t be a quick fix – even brownfield US developments can take up to three years to first production, and current prices don’t reflect the long-term project economics.

More storage capacity would help, but here, too, there are significant challenges. Where would it be located, who builds it, what access would other countries have, and could it make money with cold winters few and far between? Any new, large scale storage development would have to earn a regulated return. Alternatively, governments themselves could build strategic storage and release gas at times of crisis. The EU has intimated it will look at the options in its December gas package.

Will the crisis change how buyers purchase gas?

Yes. The surplus of gas and advent of US LNG led to a buyer’s market over the last decade. Contracts got shorter, oil indexation fell from 16%, near oil parity, to below 11% in recent years, and buyers’ portfolios took on a higher proportion of spot LNG. The likelihood is that these trends will move back the other way to a degree. The instinct will be to look for security of supply – as Chinese buyers have just done in signing longer term contracts at higher prices. Buyers may also look for more non-gas hub LNG pricing, including US Henry Hub-based contracts.

But it won’t be that simple because there’s so much uncertainty in the gas market, short and long term, and each country and every buyer’s needs are rapidly evolving. Most buyers will want to maintain a degree of portfolio flexibility which includes spot trading. The spot market has proved its worth in signalling the need for more supply. The extreme price movements indicate the market is still developing and needs more liquidity.

Are producers the big winners?

Higher revenue from spot gas sales is the icing on the cake for oil and gas producers already generating record cash flow with Brent over US$80/bbl. A single spot cargo that sold for US$20 million a year ago is worth US$250 million in today’s market.

There will be also be considerable unease. In a low carbon world, energy supply is getting more competitive. Most oil and gas producers are leaning towards gas because of its perceived sustainability compared with oil through the energy transition. The current ultra-high prices and extreme volatility do the cause no good whatsoever - the industry needs to ensure the capacity and supply is in place to meet demand. The future of gas depends on a clean product that’s both reliable and good value.