Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative turns away from coal

Renewables now dominate new projects under construction

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

What next for East Med gas?

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

-

The Edge

Walking Japan’s energy tightrope

-

The Edge

No country for oil men (and women)

-

The Edge

Battery energy storage comes of age

-

The Edge

CCUS’s breakthrough year

Yanqi Cao

Managing Consultant, Asia Pacific Power Research

Yanqi Cao

Managing Consultant, Asia Pacific Power Research

Yanqi is focused on power dispatch modelling and long-term power market dynamics forecasting for Southeast Asia.

Latest articles by Yanqi

View Yanqi Cao's full profileGavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

View Gavin Thompson's full profileAmbitious, contentious and big spending, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is 10 years old. In that time, China has splashed more than US$1 trillion on overseas infrastructure projects.

Power markets in developing economies have been major beneficiaries. But the rapid growth in much-needed generation capacity has also shone the spotlight on the initiative’s environmental impact and raised critics’ hackles over levels of indebtedness among poorer nations.

Can BRI power sector projects be judged a success? Does its record on sustainability conflict with decarbonisation goals? Can Western efforts to counter China’s influence succeed? Yanqi Cao in our APAC Power & Renewables research team takes a closer look.

What impact has the BRI had on power sector investment?

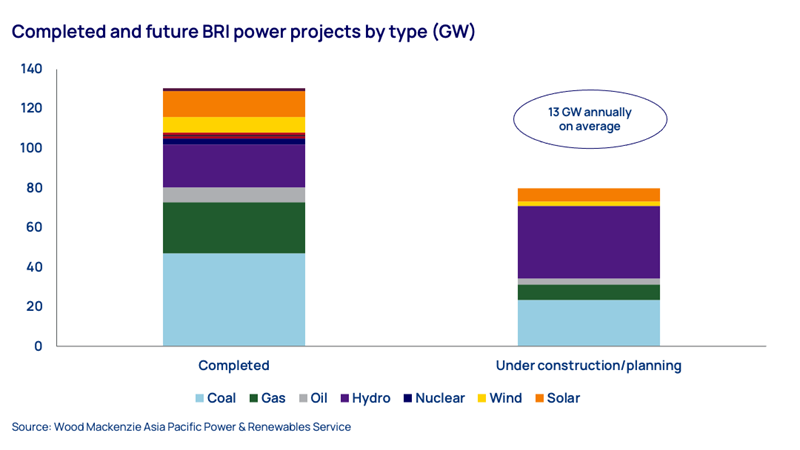

The numbers are undeniably impressive. Over the last 10 years, Chinese companies have installed 128 GW of overseas power projects – greater than the total generation capacity of the United Kingdom – with around 70% of this across South and Southeast Asia. We estimate China has financed and provided EPC services worth US$200 billion for power generation capacity worldwide, including countries that are not directly a part of the BRI, since 2013.

There is no doubt that BRI capital, technical expertise and supply chains have provided a major boost to power capacity across the developing world. But many countries have also seen debt levels soar as dollar-linked interest rates on Chinese bilateral lending have increased. In addition, massive levels of BRI lending and investment have gone into coal-fired projects, raising concerns over carbon emissions and whether these plants might be retired even while debt repayments to China continue.

Is criticism of the BRI’s environmental record justified?

Coal projects dominated in the early years. Two-thirds of Vietnam’s BRI power projects are coal-fired, while virtually all of Indonesia’s 14 GW of BRI capacity is coal.

But this has changed since China announced a ‘No new overseas coal power’ policy in 2021. Today, almost 200 BRI renewables projects are operational, accounting for 37% of total capacity – roughly equal to coal.

We estimate almost three-quarters of BRI new build projects under construction are renewables compared to less than 20% a decade ago. This is positive, but while renewables account for a growing share of projects, they remain more limited in terms of total capacity due to their smaller project size.

Has the BRI abandoned coal?

Accessing BRI finance for coal-fired projects is clearly getting tougher. Almost 90% of proposed coal-fired projects have already been cancelled due to policy changes and increased opposition to coal since 2021. This shift could impact a further 21 coal projects and we expect 13 projects at the planning stage to be shelved. China hasn’t, however, completely abandoned coal, continuing to allow coal plant equipment sales and the completion of ongoing projects.

How have Western nations responded to the BRI?

Concerned by China’s growing influence, the US, Europe and Japan have announced alternatives to the BRI. In 2021, the Biden administration, along with its G7 partners, launched Build Back Better World, which was quickly repurposed – along with more modest financial goals – as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). The PGII aims to invest US$600 billion to support developing economies, including climate and energy security. The EU has branded its efforts as the Global Gateway to provide up to €300 billion, with a key focus on clean energy projects across Asia Pacific.

These initiatives to counter China’s BRI are long on rhetoric but short on action. Western-backed investments are not only fewer, smaller and slower to market than BRI projects but must adhere to far stricter rules on sustainability and transparency. With an almost decade-long head start, the BRI’s track record of quickly delivering generation capacity matters: for cash-strapped developing economies caught between China and the West, time is money.

Where next for the BRI?

The BRI’s influence on power markets is set to grow, with a further 80 GW already under construction or at the planning stage. Adjusting its overall strategy, we expect China to place a greater emphasis on direct investment rather than the bilateral lending which dominated the BRI’s early years. Like any lender, China is attuned to the risks of debt defaults as recipients struggle to repay loans at higher interest rates.

We also expect a far greater focus on renewables. This shift is positive for emissions but not entirely altruistic. A key part of the BRI has long been to provide markets for Chinese manufacturers and equipment suppliers. With China’s solar manufacturing capacity now enough supply five times its domestic solar panel demand, that leaves a lot of hardware looking for a home.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.