Discuss your challenges with our solutions experts

Could restricting oil production in the US Gulf of Mexico lead to carbon leakage?

Federal actions have put the comparative emissions performance of the prolific US Gulf of Mexico under the spotlight

2 minute read

Mark Oberstoetter

Head of Americas (non-L48) Upstream Research

Mark Oberstoetter

Head of Americas (non-L48) Upstream Research

Mark has extensively covered the North Slope, deepwater, oil sands and unconventional sectors.

Latest articles by Mark

-

Opinion

Canada upstream: 4 things to look for in 2025

-

Opinion

Could restricting oil production in the US Gulf of Mexico lead to carbon leakage?

As one of the few major oil producing areas under federal purview, the Gulf of Mexico appears to be a focal point of President Biden’s efforts to deliver swiftly on campaign promises. But while leasing bans and increasing royalties signal fast action on the energy transition, federal actions have consequences – and they can be global.

An important and unintended consequence of enacting more restrictive policies such as a lease ban or increase in royalty rate in the Gulf of Mexico is that it could give rise to carbon leakage to countries that export crude to US. Carbon leakage occurs when the greenhouse gas emissions from industrial production are transferred outside a regulated region to another area with weaker emissions constraints in place.

Despite the growth in domestic production, the US still imports six million barrels per day (b/d) of crude oil from foreign countries. If production from the Gulf of Mexico drops, that figure is likely to increase substantially. Overall emissions will then depend on regulations and controls in the countries from which that oil is imported. In essence, climate change is a global issue and removing or handicapping a low emitter hurts the collective global average.

How emissions-intensive is the US Gulf of Mexico?

US Gulf of Mexico deepwater emissions are less intensive than all but one importer: Saudi Arabia. And more than half of the area’s 2021 production will come from a public corporation with an existing net-zero pledge.

Operators report facility emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program: these emissions totalled 4,478,780 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in 2019. This equates to 6.34 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per thousand barrels of oil equivalent (CO2e/kboe) — a decrease in intensity of 8.3% from 2011 reported levels. We forecast overall US Gulf of Mexico emissions intensity will average 19.2 tonnes CO2e/kboe in 2021.

How does that compare to other producing regions?

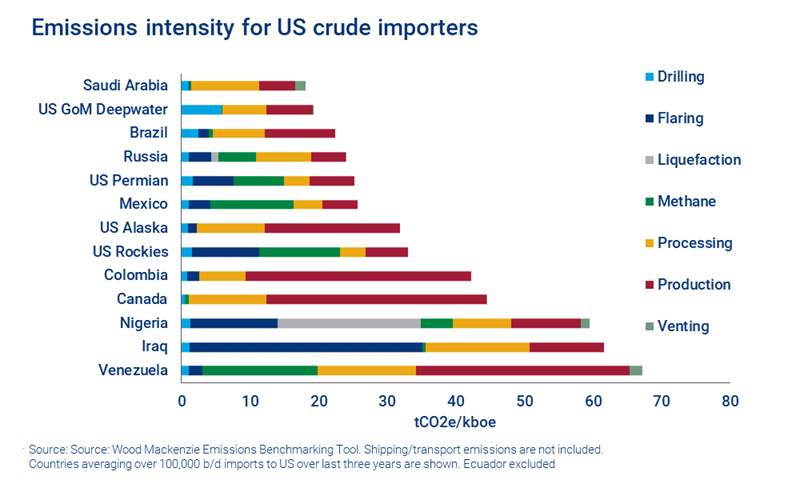

At 17th position among 72 producing countries profiled in our Emissions Benchmarking Tool, US Gulf of Mexico deepwater ranks in the first quartile and is well below both the unweighted average of 41.6 CO2e/kboe and the median figure of 26.4 CO2e/kboe.

Current US imports are mostly barrels of heavier blends required to optimise the US refining crude slate. These heavier barrels tend to have higher extraction emissions, so it is not an apples-to-apples comparison on crude qualities, but much of the crude imported has a higher emissions profile than Gulf of Mexico deepwater oil.

How would the ban affect imports?

According to Energy Information Administration data, in the period from January to November 2020 the US consumed 14.2 million b/d of crude, with imports totalling 5.9 million b/d. At the same time, the country exported 3.2 million b/d. (it’s important to note that most US exports are light crude).

In 2020, the US Gulf of Mexico produced 1.6 million b/d, or 11% of total US crude consumption. If future production declines without an equal demand response, it’s likely that either the US will become more reliant on imports, or production on US private lands would need to increase.

How can producers respond?

Expect to hear Gulf of Mexico proponents argue the case both for the economic value provided by the offshore industry and for the avoidance of carbon leakage.

A 2016 report by the US Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management could provide some support, as it concluded that removing Gulf of Mexico leases would slightly increase emissions. The report noted that “foreign sources of oil will substitute for reduced [Outer Continental Shelf] supply, and the production and transport of that foreign oil would emit more greenhouse gases”. Essentially, without a border carbon adjustment, Gulf of Mexico producers can claim lower emissions than the alternative of importing, at least under current conditions.

Is their case vulnerable?

In short, yes. Other regions are seeing increased investment in electrification and carbon sequestration. However, those major technological adoptions are not getting as much attention in the Gulf of Mexico, which faces the challenges of extreme water depths, long distances to shore and no nearby renewable power sources.

For operators in the area to remain in the top quartile of emissions intensity they will need to continuously chase improvements and keep existing platforms operating near capacity. It will also be important to ensure any improvement efforts are recognised and acknowledged in Washington.

Read our policy explainer for an in-depth explanation of what Biden’s executive orders mean for US Gulf of Mexico oil and what limits future actions. Or access analysis into the potential impact of increasing royalty rates on oil production in the area.