Can chemical recycling close the plastic loop?

Plastic is being demonised – innovative circular processes could be its salvation

1 minute read

Olivia Loa

Research Analyst, Global Chemicals

Olivia Loa

Research Analyst, Global Chemicals

Olivia has experience across the energy value chain, from upstream oil and gas to chemicals and renewables.

View Olivia Loa's full profileReduce, reuse, recycle is all very well in theory, but when it comes to the latter, only certain types of plastic can be handled by existing mechanical processes. Could emerging technology such as feedstock recycling, chemical depolymerisation and solvent purification offer a solution?

Our report Chemical recycling: breaking down the current landscape examines the potential for ‘plastic to plastic’ and ‘plastic to fuels’ chemical processes to pull significantly more material into the circular economy. Fill in the form to download a complimentary copy of the report, or read on for an introduction to the topic.

What’s the problem?

The issue of plastic waste may have captured the world’s attention recently, but plastics remain vital to the global economy. While global demand growth for plastic packaging is expected to slow down over the coming decades, the quantity of plastic waste created in 2040 will still be nearly double the amount today. Higher levels of recycling are therefore badly needed to avoid even more plastic polluting the environment. But traditional mechanical recycling, which breaks down plastic into small pellets but retains a polymer’s natural structure, is only suitable for certain types of packaging and use cases.

What are the benefits of chemical recycling?

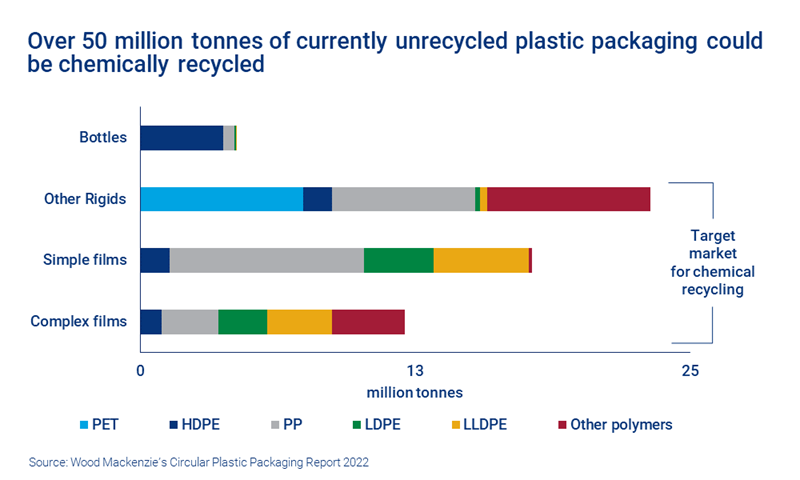

Chemical processes have the potential to capture over 50 million tonnes of plastic packaging waste currently considered ‘non-recyclable’. Suitable material includes ‘other rigids’ (rigid packaging other than bottles), simple films and even complex films (film comprised of different layers of materials and/or coatings). The potential to recycle a wider range of plastics can also incentivise overall collection rates for plastic waste.

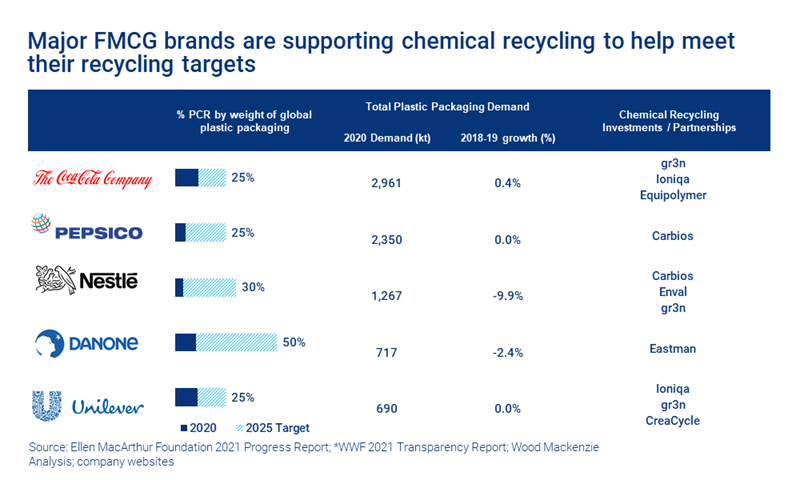

What’s more, chemical recycling results in virgin-quality material that’s suitable for higher value end-use applications. It’s also more tolerant of low-quality waste and results in lower process loss due to its ability to process a diverse range of input material. Various big brands support chemical recycling and are already collaborating with recyclers, including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé, Danone and Unilever.

What use cases are there for chemically recycled plastic?

Chemical recycling can take several forms. Feedstock recycling involves heating plastic waste to produce hydrocarbon products or syngas. Plastic waste can also be broken down chemically into its building blocks or monomers, in a process known as depolymerisation. Or it can be dissolved in a solvent to extract virgin-quality polymer.

Feedstock recycling is already well-positioned for commercial ramp-up and offers a significant cost advantage. Meanwhile, depolymerisation shows the most promise in tackling the key challenge of providing food-grade recycled containers. Development of solvent purification is currently lagging, but in theory it provides the quickest and simplest path for plastic waste to re-enter the value chain at a higher quality than mechanical recycling.

What are the challenges involved?

While chemical recycling shows a lot of promise, there are some obstacles to widespread uptake. One issue is that chemical recycling is more carbon intensive than mechanical recycling. Yield may also struggle under commercial operations. However, one of the largest challenges is simply getting access to sufficient raw materials in the form of bale feedstocks.

A gap between bale supply and demand has existed since China enacted its National Sword policy in 2018. This banned the import of most plastics headed for the country’s reprocessing facilities. Given that China had previously handled nearly half of the world’s recyclable waste, the result has been an increase in plastic ending up in landfill, incinerators or littering the environment.

How can the issues be overcome?

More widespread collection and improved infrastructure in the form of materials recovery facilities are badly needed. Funding could potentially come from environmental legislation, such as extended producer responsibility (EPR) and plastic levies. Consistent regulation across geographies will also have a critical role in reducing the barriers to entry for chemical recycling and fostering stakeholder collaboration.

Don’t forget to fill in the form to get the full report. This includes deeper analysis of projects status and cost considerations for each technology, the developing regulatory environment, and the outlook for adoption.