1 minute read

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Over 30 years, Graham has advised on taxation matters and supported complex fiscal negotiations.

Latest articles by Graham

-

Featured

Upstream fiscal 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Featured

Energy fiscal policy 2024 outlook

-

Featured

Conflicting ambitions will shape the upstream fiscal landscape in 2023 | 2023 outlook

-

Opinion

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

-

Featured

Stage set for tougher fiscal terms for upstream operators in 2022 | 2022 outlook

Investors remain perplexed by the US tight oil phenomenon. But the economics of tight oil actually has all the characteristics of conventional deepwater developments.

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Over 30 years, Graham has advised on taxation matters and supported complex fiscal negotiations.

Latest articles by Graham

-

Featured

Upstream fiscal 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Featured

Energy fiscal policy 2024 outlook

-

Featured

Conflicting ambitions will shape the upstream fiscal landscape in 2023 | 2023 outlook

-

Opinion

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

-

Featured

Stage set for tougher fiscal terms for upstream operators in 2022 | 2022 outlook

US tight oil and global conventional deepwater plays are hot property. Some companies – and their financial backers – are wedded to one or the other. Others seek a diverse portfolio and invest in both.

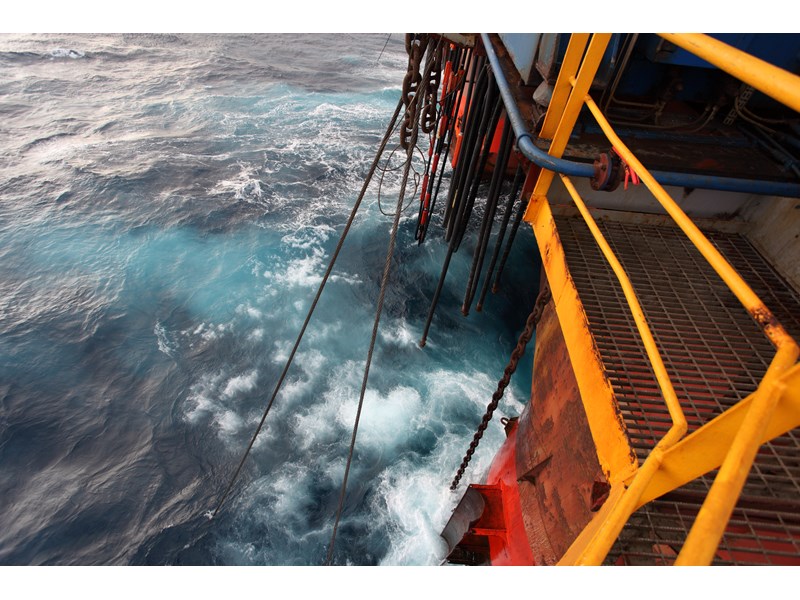

Tight oil is where the bigger opportunities lie. We expect tight oil plays to contribute 10.5 million b/d, or half of the new oil supply needed to meet demand over the next 10 years. Deepwater pre-FID projects, very much the domain of Big Oil, will deliver 5.3 million b/d from the handful of deepwater provinces that are ‘in the money’.

Tight oil on the up, while deepwater took a dive

Since the price downturn in 2014, the investment community has mostly been up on tight oil and down on deepwater.

Tight oil is regarded as cheap and low risk with a ‘switch-on, switch-off’ investment profile. By contrast, deepwater is very expensive, high risk and an ‘all or nothing’ investment call. Few investors have been willing to roll such big dice recently.

Moving closer together

But in the first part of our three-part series, we concluded that the industrialisation of tight oil and the introduction of faster, smaller deepwater development schemes means that these two opportunities have become more similar.

Deepwater has moved to slim down and shorten its investment cycle. In contrast, the Permian has gone the other way, scaling up capital spend, project footprint and value extraction. As a result, some long-held industry assumptions no longer hold true.

While the nature of deepwater hasn't fundamentally changed, the investment proposition has.

Angus Rodger

Vice President, SME Upstream APAC & Middle East

Angus leads our benchmark analysis of global Pre-FID delays, and deep water developments.

Latest articles by Angus

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

-

Featured

Upstream oil & gas regions 2025 outlook

-

Opinion

How to make upstream licensing work

-

The Edge

What’s driving the upstream revival in Southeast Asia?

-

Opinion

A two-decade decline in exploration is driving the need for carbon neutral investment in Australia’s upstream sector

-

Opinion

Asia Pacific upstream: 5 things to look for in 2024

Consider the full-cycle costs

In part one, we highlighted that the expenditure and cash flow profiles of these very different play types are converging. Our latest report takes that a step further: what happens if we use the same investment metrics to evaluate both?

Tight oil costs are usually presented on a well-only basis. But tight oil is about more than just well performance. In contrast, deepwater economics are usually assessed on a full-cycle basis, and rightly so: a deepwater well simply can’t exist without the surrounding infrastructure.

When we compare them, a full-cycle deepwater project has a much lower IRR than a tight oil well.

But if tight oil wells are so profitable, why is Tight Oil Inc struggling to generate free cash flow?

Our analysis shows that half-cycle tight oil well economics are meaningless. So, what do investors need to consider when comparing two opportunities? And if IRR is misleading, what metrics should they use? Fill in the form on this page to get an extract of the report.