Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

How the world gets onto a 1.5 °C pathway

Investment in energy supply must increase to US$2.7 trillion a year

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Tariffs - implications for the oil and gas sector

-

The Edge

Big Mining pivots to copper for growth

-

The Edge

What a future Ukraine peace deal means for energy (Part 2)

-

The Edge

What a future Ukraine peace deal means for energy (part 1)

-

The Edge

How gas could displace renewables in meeting surging US data centre demand

-

The Edge

Majors' capital allocation in a stuttering energy transition

Prakash Sharma

Vice President, Head of Scenarios and Technologies

Prakash Sharma

Vice President, Head of Scenarios and Technologies

Prakash leads a team of analysts designing research for the energy transition.

View Prakash Sharma's full profileDavid Brown

Director, Energy Transition Practice

David Brown

Director, Energy Transition Practice

David is a key author of our Energy Transition Outlook and Accelerated Energy Transition Scenarios.

Latest articles by David

-

Opinion

Energy transition outlook: Americas

-

Opinion

The federal government steps up support for nuclear power

-

Opinion

The impact of Republican control on US energy policy and the IRA

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

-

The Edge

COP28 key takeaways

-

The Edge

How the world gets onto a 1.5 °C pathway

Jom Madan

Senior Research Analyst, Scenarios & Technologies

Jom Madan

Senior Research Analyst, Scenarios & Technologies

Jom works on scenario modelling for country and global-level energy mixes across all major energy commodities

View Jom Madan 's full profileLindsey Entwistle

Senior Research Analyst, Energy Transition

Lindsey Entwistle

Senior Research Analyst, Energy Transition

Lindsey provides analysis and insights into global policy, regulations and disruptive technologies.

View Lindsey Entwistle's full profileRoshna N

Research Analyst, Energy Transition

Roshna N

Research Analyst, Energy Transition

Roshna N specialises in integrated energy and emission models for Asia-Pacific and African markets.

Latest articles by Roshna

-

Opinion

Energy transition outlook: Asia Pacific

-

Opinion

Energy transition outlook: Africa

-

The Edge

How the world gets onto a 1.5 °C pathway

-

Opinion

What would it take for India to reach net zero emissions?

Sarah Jameson

Lead Data Analyst, Scenarios and Technologies

Sarah Jameson

Lead Data Analyst, Scenarios and Technologies

Sarah is the technical expert for our energy transition outlook scenario modelling

Latest articles by Sarah

View Sarah Jameson 's full profileThe energy transition isn’t going to plan. The Paris Agreement of 2016 – which aims to limit the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 – is looking less and less achievable.

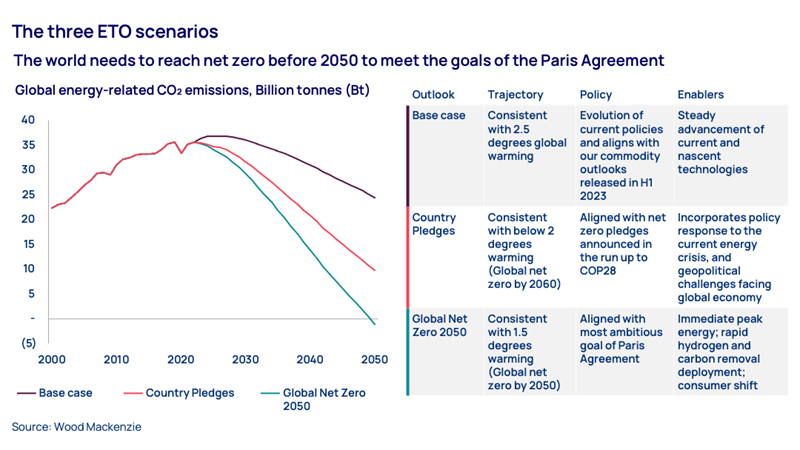

The base case in WoodMac’s fifth annual Energy Transition Outlook, released last week, suggests that the world is on a 2.5 °C pathway. A degree off may not sound much but the scale of the challenge to close the gap cannot be overstated – nor the catastrophic implications of failing to do so.

Our base case represents the evolution of current policies and a steady advancement of low-carbon technologies. Prakash Sharma and the team* compare the base case with two scenarios – Country Pledges, in line with a 2.0 °C pathway, and Global Net Zero, a 1.5 °C pathway. They talked me through where we are and what has to change.

First, the world is not on track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C or even 2 °C. Why? The Net Zero pathway was never going to be easy but the war in Ukraine has underlined the extent to which the global economy still depends on fossil fuels for energy security. Oil, gas and coal today supply 80% of the world’s energy needs. While the supply of low-carbon energy has grown by one-third since 2015, global energy demand has grown faster still, propelled in the last two years by the bounceback from the Covid-19 lows.

The depressing conclusion of our analysis is that global emissions will continue to rise, reaching a peak in 2027, and won’t fall below 2022 levels for nearly a decade.

Even so, the base case hints at the momentous shift already underway towards an electricity-dominated energy system, complemented by the scaling-up of diverse low-carbon technologies, including carbon sequestration. Electricity’s share of energy rises from 20% to 30% by 2050, the global stock of EVs increases from 43 million to over 1 billion EVs, while hydrogen becomes mainstream, reaching a 4% share of the energy market. Progress, but it’s not happening quickly enough.

Second, the goal of sustainability is alive and kicking. Achieving a 1.5 °C pathway will be extremely challenging, but still possible if the world is prepared to act this decade.

Policy is framing the way forward. The US Inflation Reduction Act and Europe’s REPowerEU have announced generous incentives and targeted policies to promote new technologies. Japan, South Korea, China, Canada and India are following suit. Policy has widened to support the build-out of the domestic supply chains for low-carbon technologies to bolster energy security and reduce dependence on China.

In our 1.5 °C scenario, the transformation of energy supply is much faster, with low-carbon energy pushing out fossil fuels. Electricity demand triples by 2050, solar and wind capacity increases from about 2,000 GW today to more than 18,000 GW in 2050. Hydrogen becomes mainstream, capturing an 11% share of final energy demand.

In contrast, fossil fuels’ share of supply falls to 30% from 80% today. Residual emissions from fossil fuels are largely offset by scaling up CCUS and direct air capture to 7 Bt of captured volumes, three and a half times the base case. By 2050, oil demand falls to just 30 million b/d in 2050 compared with 90 million b/d in the base case. Gas is more resilient, displacing higher carbon-intensive coal in the power sector, particularly in developing economies when paired with CCUS. Unabated coal-fired power generation by 2050 is negligible.

Third, to get the world onto a 1.5 °C pathway requires low-carbon technologies and infrastructure to scale up much faster than is happening at present. An effective global carbon price and a ramp-up in investment are two game changers. A carbon price of up to US$200/tonne, eight times higher than today’s global average, would drive the adoption of low-carbon technology in hard-to-abate sectors such as steel, cement and chemicals.

We estimate investment in energy supply needs to increase by 50% to US$2.7 trillion a year through 2050 to achieve a 1.5 °C pathway. But it’s not just about more money. Building a sustainable future will mean reallocating capital away from fossil fuels into low-carbon supply, related infrastructure and raw material supply chains.

In 2030, the world may still be emitting about 36 Bt of energy-related CO2 emissions, the same level as today. But to get on a 1.5 °C pathway, we need emissions to peak immediately – not in seven years – and to fall by at least 16% by 2030, declining precipitously thereafter across all sectors.

For all this to happen, COP28 in December must be a catalyst for global cooperation, setting the institutional framework to increase capital allocation, drive innovation and develop new technologies.

Wood Mackenzie’s ETO provides a unique perspective on how energy markets will evolve based on our granular analysis of demand and supply, country-by-country and asset-by-asset, across oil and gas, power and renewables and metals and mining.

* Our ETO authors include David Brown, Jom Madan, Lindsey Entwistle, Roshna N, and Sarah Jameson.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world. Sign up today using the form at the top of the page to get The Edge delivered to your inbox.