Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

COP29 faces climate finance challenge

Capital flows to lower-income countries are seen as essential for agreement on emissions reduction

8 minute read

Ed Crooks

Senior Vice President, Thought Leadership Executive, Americas

Ed Crooks

Senior Vice President, Thought Leadership Executive, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Bonus episode from COP29: Getting real about methane emissions

-

Opinion

US LNG a test case for the Trump administration’s ambitions

-

Opinion

What happened at COP29?

-

Opinion

The Trump administration's AI strategy points to strong growth in US power

-

The Edge

COP29 key takeaways

-

Opinion

Live from COP29 – One weird trick to solve our energy problem

UN climate talks, intended to set a course for the world economy and ecosystem for decades to come, are often shaped by what has happened in the past few weeks. For COP29, which began on Monday in Baku, Azerbaijan, the overshadowing event was the re-election of former President Donald Trump, who has promised to take the US back out of the Paris climate agreement.

The US has been in a revolving door on Paris since the text was negotiated in 2015. Successive administrations signed up in 2016, announced withdrawal in 2017, formally left in 2020, and then rejoined in 2021. Now a new administration is set to begin the exit process again, starting next January.

The US election result is a blow to hopes of co-ordinated international action to accelerate the transition to low-carbon energy. The talks in Baku have been called “the finance COP”, because the principal objective is securing a global deal on climate finance: flows of investment, loans and grants from rich countries to low and middle-income countries, to support the deployment of low-carbon technologies and to build resilience to climate impacts. As the conference begins, it is far from clear whether that objective can be achieved over the next two weeks.

A deal on climate finance would be significant both because it would accelerate investment in low-carbon energy in emerging economies, and because it would be a beacon of international cooperation. Advocates for action hope that if low and middle-income countries see that rich countries are prepared to help them face the climate challenge, they will be more willing to commit to ambitious curbs on emissions.

A new round of emissions commitments, known as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is scheduled to be delivered in time for COP30 in Brazil next year. António Guterres, secretary-general of the UN, used his speech at the opening ceremony to remind world leaders that to limit global warming to 1.5 °C, the goal set in the Paris agreement, global emissions need to start falling immediately at a rate of 9% a year. (They are currently rising.)

The principle may be sound; the practice is challenging. Behind the scenes of the conference, there are intense debates over who should contribute and who should receive funds, how flows are reported, the role of carbon markets, and what types of finance should be counted towards international goals.

The aim is to agree what is known in UN jargon as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance. It is new relative to the old collective goal, agreed back in 2009, for US$100 billion a year to flow from richer to poorer countries in investment, loans and grants. The world took 13 years to reach that goal, which was first hit in 2022, and now negotiators are attempting to agree a much more ambitious objective of US$1 trillion a year or more.

The scale of the challenge is underlined by the shortage of high-profile political figures visiting the talks. COP28 in Dubai last year was attended by world leaders including Narenda Modi, India’s prime minister, Emmanuel Macron, president of France, and Kamala Harris, vice-president of the US. None of them is expected to come to Baku.

Speaking at the COP29 opening ceremony on Monday, Simon Stiell, the executive secretary of UN Climate Change, did not try to conceal the fact that the talks faced an uphill battle, but struck a positive tone. “In tough times, up against difficult tasks, I don’t go in for hopes and dreams,” he said. “Now is the time to show that global cooperation is not down for the count.”

The next two weeks will show whether that positive outlook is justified.

The Wood Mackenzie view

The US’s turbulent relationship with the Paris agreement is both a symptom and a cause of emerging tensions over the pace of the global transition to low-carbon energy.

Wood Mackenzie’s new energy transition outlook, published last month, concludes that the world is running out of time to reach net zero emissions. No large countries are on track to meet their 2030 emissions goals. And although the 2050 targets remain in reach, they can be achieved only with a sharp acceleration in investment.

In Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast, the world invests a total of about US$55 trillion in energy and natural resources by 2050 To get on a trajectory to reach net zero emissions by mid-century, a pathway consistent with the Paris goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, that investment would have to be increased by about 40%, to US$78 trillion.

Wood Mackenzie’s outlook also includes what we call a “delayed transition” scenario, showing possible outcomes if the uptake of low-carbon technologies including renewable energy and electric vehicles is slower. Failure to reach a meaningful climate finance deal at COP29 would make it more likely that the world will move on to that pathway.

President-elect Donald Trump’s victory in last week’s election is another factor nudging the world towards that delayed transition. China’s powerful influence on the global transition, driving down costs for solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles, will continue unabated. But for the US, deployments of renewable energy and sales of EVs are likely to be slower.

Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast puts the world on course for about 2.5 °C of warming by the end of the century, which is already well above the Paris goal. The delayed transition scenario implies about 3 °C of warming, and the risks of that outcome are clearly growing.

The UN’s Simon Stiell said in Baku: “We mustn’t let 1.5 [degrees] slip out of reach”. Answering his call will take a radical change in direction for the world.

When COP29 concludes next week, the best-case outcome for supporters of climate action would be an agreement that more than US$1 trillion a year will flow in climate finance, adding together investment, lending and aid payments. (A total of US$1.3 trillion has been rumoured to be under negotiation.) That would allow advocates to argue that the UN process for tackling climate change is still alive and making progress. Failure will be taken as a sign that the entire effort to agree coordinated international action on climate is faltering.

Keep up with the latest from COP29

I am in Baku recording a series of podcasts for the Energy Gang, bringing you all the latest developments from the talks. Follow us on WoodMac.com, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In brief

Nissan plans to cut 9,000 jobs and 20% of its manufacturing capacity worldwide, as it struggles to compete in the Chinese and US markets. Wood Mackenzie analysts said one of its biggest problems was stiff competition from Chinese manufacturers, particularly in hybrids and battery electric vehicles. The company also blamed its lack hybrid models in the US market.

The US Strategic Petroleum Reserve has completed its final scheduled purchase of crude oil. It has now directly purchased 59 million barrels, and cancelled planned sales for a further 140 million barrels. The purchases were made at an average price of less than US$76 per barrel, compared to an average selling price of about US$95 a barrel for the 180 million barrels sold in 2022 under an emergency declaration authorised by President Joe Biden following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Other views

A second Trump administration, and what it means for energy and natural resources – Simon Flowers

Is the crude oil refining sector delivering on decarbonisation? – Iván Pérez

Copper rush: A strategic analysis – James Whiteside and others

Five ways to disaster-proof the energy grid – Amy Myers Jaffe

Quote of the week

“It’s actually a scandal, I think, that the federal government has not — at one point, with all the money that we spend on defense and everything else — just said, we’re going to spend $15 billion to buy enough power transformers to have a backup for every transformer in the country.”

JD Vance, the Vice-President elect, argued on the Joe Rogan podcast that the US should build a strategic reserve of electricity transformers to strengthen the resilience of the grid to threats such as attacks from electromagnetic pulse weapons.

The issues around the availability of transformers, and some of the potential pitfalls with the idea of building a strategic reserve, were discussed in a recent episode of Wood Mackenzie’s podcast The Energy Gang.

Chart of the week

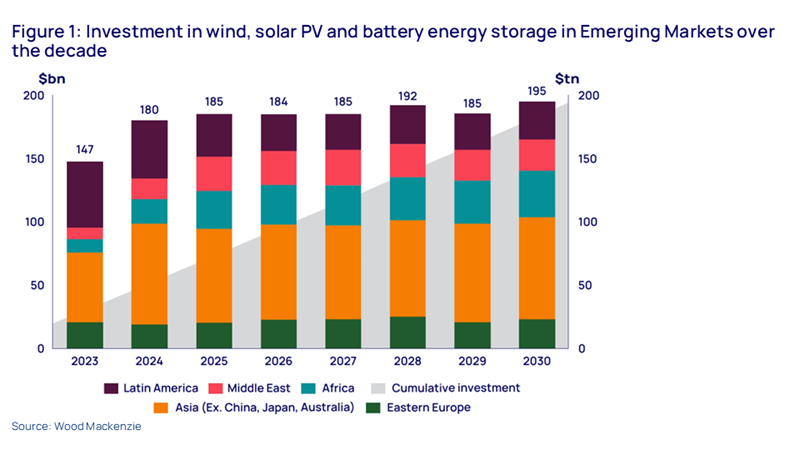

This comes from a recent Wood Mackenzie paper on the issue that is at the top of the agenda for COP29: climate finance. The paper, a short ebook titled ‘Unlocking renewable energy financing in emerging markets’, is written by Daniel Tipping, a Managing Consultant in our Power & Renewables Consulting practice for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

The paper argues that emerging markets are well-positioned to leapfrog traditional fossil fuel-based energy systems and adopt cleaner, more sustainable alternatives, and Wood Mackenzie’s forecasts reflect that. The chart shows our projections for investment in wind, solar and battery storage in emerging markets out to the end of the decade. And as you can see, the numbers run in the range of US$180 billion to US$195 billion every year to 2030.

Wood Mackenzie’s Tipping adds: “To call the low carbon renewable financing opportunity in emerging markets over the remainder of this decade ‘significant’ is an understatement.”

Get The Inside Track

Ed Crooks’ Energy Pulse is featured in our weekly newsletter, alongside more news and views from our global energy and natural resources experts. Sign up today via the form at the top of the page to ensure you don’t miss a thing.